On Desiring Non-Desire

If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world. —C. S. Lewis

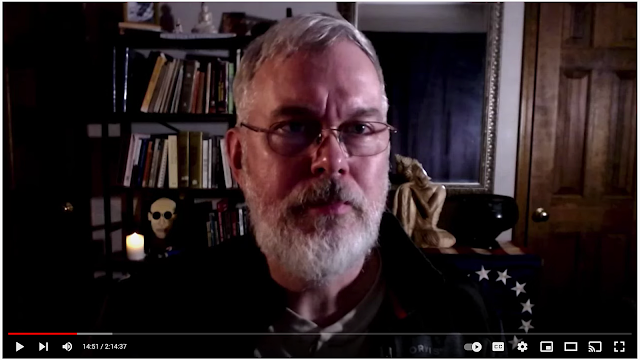

In my most recent Q&A video (Question and Answer #39, which is here), a person mysteriously named Pseudonym asked the following question:

One very simplistic critique of Buddhism is noting the contradiction that “you desire to not desire”. Similarly, practicing Buddhism to reduce stress, be happier, or even to seek enlightenment as an achievement to tackle are misguided. Yet, enlightenment remains as the target (or perhaps the object of desire) of Buddhist practice. Is this a real contradiction, or in what ways is this critique missing the mark? Can you help untangle this knot?

I did my best to answer the question, which starts at the timestamp of around 15:05, along with many others, and subsequently a viewer of the video expressed some appreciation for that answer in particular and wished he had a transcript of it to study it; and so I have taken the trouble to transcribe the answer in question. What follows is that transcript, which I hope will be of some value to some of you good folks.

I am always humbled, maybe even very mildly appalled, when I transcribe something I said in a video, because of all the illiterate (or unliterary) ums, and you knows, and kind ofs, and so on. I’ve edited out some of the more egregious stammering but have left in enough to make it plain that this is a transcription of a spontaneous, off the cuff answer. I hope you don’t mind.

*****

Well, not all monks, even—I mean let’s just set aside the drones and the clowns and the crooks and, you know, just the lazy people that, you know, they’re not really even trying. Just set those aside. They do exist in the Sangha; we’ll just ignore those. But even the seriously practicing monks, not all of them, are like, striving for this goal of Nibbana. Because some of them, it’s just they feel like it’s a duty to practice. You know, it’s their sacred duty to practice Dhamma as well as they can, so that is, you know, that’s like their goal is just practice as well as they can. Some people, they just like to meditate, they like to live a simple, austere life—that was pretty much my situation. And so they just practice because of that.

I have warned for many years, I mean, beware of goal-oriented Dharma. You know, if you’re not in the present moment but you’re like, aiming at something in the distant future, or maybe even the near future, so long as you’re not here in the present moment then you’re not practicing correctly. I mean if you’re doing this in order to get something later…then, yeah, I mean you’re already misguided to some degree.

Which reminds me of, I think it’s one of the last, um, I can’t remember what they’re—in Spinoza’s Ethics, you know, he’s got it set up like Euclid; so it’s one of the last theorems or whatever it is that you prove in geometry, that um, virtue is its own reward. You’re not being virtuous in order to get into heaven or whatever, it’s just virtue is its own reward. And Dhamma practice really is its own reward.

And so long as you retain that kind of attitude, your Dhamma practice will be more fruitful, I think. Not that you should be doing it in order for the Dhamma practice to be more fruitful.

But still, there are a lot of monks who are striving ardently, earnestly for Nibbana or Nirvana or Enlightenment. And the thing is, the more you progress—and we’ll get to this later on, there’s another question if I remember correctly, that kind of, uh, applies to this—where if, let’s say, you’re striving for Enlightenment, just single-mindedly, you know, and so all your other cravings kind of go away, or, you know, or, they’re sublimated or they’re just, you know, rejected, or whatever, and you’ve got this one craving left. You don’t crave girls anymore, you don’t crave rock ’n’ roll and ice cream and partying with your old friends, you’re not craving a book collection [pointing back at my book collection]…um, you know, all you want is Enlightenment.

And so you’ve reduced the number of your attachments and desires down to this one big one, and then you try and you try and you try, but because you still have this clinging, you can’t become enlightened. Because that’s like your last obstacle. So eventually you get to this point—it could be like, uh, an insight moment where you just realize, you just let everything go; or it could just be like absolute despair. You know: “I just can’t do this anymore.” You just kind of cast it away, and that’s it, I mean you’ve thrown away the last attachment. So Enlightenment can happen that way.

So, on the one hand you’re better off not setting up a goal as a purpose for practicing. It works for some people I suppose, if we go to the second route that I’ve just explained, where it’s this thing, this last attachment, you know, you sublimate all of your other attachments for this one holy, sacred ideal, and then of course because you have the attachment you can’t get there; you can’t attain it. And then finally for whatever reason, positive or negative, you cast that aside too and…click. So that can work too.

But um, yeah, desiring not to desire—I mean, it can kind of work, it can move you in that direction, but of course, obviously, if you’re desiring not to desire you’re never going to reach non-desire, until you eventually cast aside the desire not to desire; and that may be at a relatively advanced level. So that can happen too.

So I’ll just move on to the next question….

This exact question and its variations were even asked during the Buddha's time and it is well answered in SN51.15 and AN 4.159. You desire Awakening, then when you are going to reach it, you no longer desire it because you have it. Desire for Awakening is last or one of the last desires to be overcome. Not all desires are equally unwholesome. You let go of worst ones, then less blameworthy and so eventually you let go of even the highest desire, desire for awakening. Furthermore, you can even use conceit up to a certain point. You feel jealous that such-and-such is Awakened, ("why can't I reach what s/he can? Why am I worse?") you practice and when you reach Awakening yourself, you drop it as well.

ReplyDeleteIt is a gradual path when as you step on a higher step, you let go of the previous one. One by one...

https://i.imgflip.com/78qcfj.jpg

ReplyDelete