My Father’s Paranormal Childhood

"FREEDOM"—yells the orator, while the banner of the free

Floats high, serene, in majesty o'er the Penitentiary;

"Peace, Brother!" screams the Flower Child parading through the town,

"Give us peace, you motherfuckers, or we'll burn the bastard down!"

When giving an account of how I came to be a Buddhist monk, or a strange person in general, I tend to begin my explanation with the statement that I had a weird father. He was definitely weird—among other things he was a warlock, hypnotist, and trainer of spirit mediums who could see ghosts and auras. He also wrote a lot, including some poetry, of which the above stanza is a small excerpt. But in addition to poetry he also wrote a kind of spiritual autobiography, which at present is unpublished. It’s one of the few material things I inherited from him after he died.

So, as a kind of taste or teaser of his unpublished little book, I include below the first chapter of it, recounting his childhood in the deep south during the 1920s and 30s. It also includes some social commentary, including some anti-racist statements which were typical of my father—people who grew up in the deep south before the Civil Rights Movement were not all horrible racists, and many blacks lived happy and fulfilling lives, even then, even there. I would imagine that even a few slaves in pre-Civil War times lived happy lives…though we needn’t wade into that.

Mind you, this chapter in his Life was long before he began experimenting with the Occult, as he called it. But you can see how he lived in a world surrounded by invisible forces, and influenced by them, even then.

Would You Reap the Wind, by John Reynolds

Chapter 1: An Unusual Youth

I learned at my mother's knee that for the slightest infractions of the rules, God – a ferocious man in the sky – would strike me dead with thunder and burn my miserable soul in Hell's fire forever and ever, Amen. For real heinous offenses like sassing your Ma, he would break your back first, since it was in Holy Writ that sparing the rod would spoil the child. She, God's firm right hand, backed up said Law with her favorite weapon – the ironing cord – for the good of my soul.

My father, a very gentle, loving man, had a gentle, loving God.

So I observed at an early age that vicious people had vicious Gods, vicious dogs, and vicious children; and gentle people had gentle Gods, gentle dogs, and gentle children.

They attended the same Southern Baptist Church and worshipped a Southern Baptist God and everyone who did not was an unsaved sinner separated from the Lord by the sin in his heart. While still in my teens I rebelled against her and against her God and would roll my eyes toward Heaven and commit the ultimate sacrilege, saying, "Go ahead, God, strike me dead, don't disappoint her" – and then take my beating.

My father was a school teacher, an ordained Baptist minister, and had also been admitted to the Bar. He taught at Martha Berry School at Possum Trot, Georgia, near Rome, a religious boarding institution where you could start in the first grade and go clear through college without changing schools. The Bible was a textbook. They had a 35,000 acre campus. The boys' high school and the girls' high school were five miles apart. People sent their children there to keep them out of jail.

My uncle Gideon, a blacksmith, gave me my real moral values. There were only two. Things a real man will not do: fight a cripple, or beat on cold iron – a cripple being a physical or intellectual inferior, and beating cold iron meaning belaboring a hopeless situation of any kind.

Since I was a campus brat, Dr. Reynolds's son, I could never be accepted as one of the boys until I proved that I was the biggest misfit in the bunch. So, I established a pattern that has lasted me most of my life – glorying in my misdeeds, so I can be one of those Men among Men.

I never once ever considered myself an abused child; almost all children of my generation were abused children by today's standards. I got no more beatings than the kids I ran with, indeed fewer than some; and my mother had her redeeming features: To prowl the woods and mountains for days on end was OK, and I got my first rifle, a .22, at age eight, when most of my friends had only BB guns.

I never got a licking for fighting, only for losing – makes you try harder next time. Going to the doctor happened when you got born and again when you died, sometimes.

When I was eight, I was kicked in the head by a horse. They took me to the school nurse who pronounced that I wasn't hurt very much. Later X-rays, after I was grown, showed it was broken like an egg. The next year I was chopped in the head with a mattock – another head injury, this time a depression fracture. Again the school nurse took a few stitches and pronounced me alive. Again, no doctor. Kids have got to be tough. I don't know if one, both, or neither of these injuries had anything to do with it, but it was about this time that I started seeing auras and found that it gave me an advantage over others: I can't say I knew their thoughts, but I sure could see their moods. I could tell when they lied, were ill at ease, frightened – and later in life when they were bluffing. It sure gave me an edge playing poker.

My father had a firm belief in mental telepathy from an experience he had as a young man. (He was 46 when I was born.) As a young man he had practiced Law in Little Rock, Arkansas. His first wife and young son died of malaria. My sister Charlotte was in delicate health, and the doctors advised him to take her away from the low fever country and back to the mountains or he was going to lose her too. So he decided to move back to the North Georgia mountains where he had been raised as a boy.

He had a brother-in-law, John Wallace, also a widower with two sons, who accompanied him on the train as far as Memphis, Tennessee. John Wallace was his closest friend; he was also a periodic alcoholic, and Memphis was his favorite watering hole. My father advised him, "John, finish up your business and go home or you will get mixed up with your old crowd again and all kicked out of shape for weeks. Give yourself a break and go home." John promised faithfully that he would.

On his second night home my dad woke up from a sound sleep with the words "JOHN WALLACE NEEDS YOU" over and over like a telegraph in his brain. He was so upset by this that he could not get back to sleep. A few days after this he received a letter from his and John's mother-in-law. She asked what had happened to John; he hadn't come home. A day later he got her second letter: John Wallace had been killed in a barroom brawl on the same night, at about the same time, that Dad had received the message. He was a believer in mental telepathy all his life after that. My father was not given to tall tales or even exaggeration. I was raised on this story and firmly believe it to be true.

I was about ten when there was an article in the Sunday magazine section of the Atlanta Constitution about some mind over matter experiments some college professors were playing with. The paraphernalia was simple: You take a large cork – this is important for insulation – and you stick a sewing needle into it point up. Then take a piece of hard-finish tissue paper (we used onionskin typing paper), a piece four inches square, and fold it corner to corner and again corner to corner till it peaks up like a little pyramid. Balance it on the point of the needle, point up. Focus your eyes on the point and concentrate on motion. Some people can really make it spin, and others not at all. Women usually make it spin in one direction and men the other – though some like my dad could spin it one way, break it, and then spin it the other way. It was during these experiments that I learned to narrow my mind into a narrow beam and increase its power, like turning the nozzle of a garden hose, tightening it from a wide spray to a forceful narrow stream. At eleven years of age I started high school, where I had a ball by beaming thoughts at other boys during study hall and starting waves of coughing or running for the bathroom. My English teacher, Mrs. Titrud, or "Ma Tit," depending on if she was within earshot, figured out that I was doing something, but didn't know what. She was, I think, a bit psychic. She could see through me where the others couldn't. I did this thing with chalk while writing on the blackboard: I'd be sure the teacher was looking the other way, then I'd take my thumb and thump a piece of chalk like shooting a marble, and make it spatter on the blackboard near my face, and then glare at some kid in the class like he did it and watch him catch hell. When Ma Tit caught a kid goofing off, she would grab a handful of hair and slap the ears half off his head. I tried it in her class one time too many: she headed for the kid I was glaring at, stopped, and whirled around and grabbed my hair, and there went my ears. I always passed her English class because I was afraid to fail. She was the first female preacher I knew. I doubted the wisdom of God as a kid, for wanting her to preach his holy word.

When I was fifteen my father's contract was not renewed, as it was in the middle 30's and times were hard. We moved to the village of Cave Spring, where I went to school with girls. Cave Spring was a whole new world, not at all like the campus at Berry.

At the old school I had little need for money. Where would one spend it? Now I learned to hustle. I did chores for 15 cents an hour – got a paper route – worked for a landscape gardener who paid 20 cents an hour – relief lifeguarded at the swimming pool – gigged frogs and got 20 cents a pound for legs.

As a new kid I was an outsider, so I made a buddy out of James, who let's say was different. We were fifteen and I a senior in high school, James still in the sixth grade, his fourth year there. James was fat and wore glasses with thick lenses. He didn't talk much and before I arrived had no friends. Different I think was not the right word – James was downright strange. Bees would not sting him. Snakes would not bite him. I saw him catch bees and wasps and cup them in his hands, careful not to hurt them, then hold them up to his ear and listen to them buzz, and then turn them loose again. The first time I saw him pick up a cottonmouth moccasin and gently stroke it – it shook me.

He would not go fishing if the fish were not biting that day, and if I went without him I would catch no fish.

"How do you know the fish aren't biting, James?"

"I don't know, I guess it just ain't a fish bite'n day."

"How do you know the fish aren't biting?"

"You didn't catch any, did you? I just know."

Once I saw him eating poison ivy buds in the early spring. "You're gonna get that stuff in your mouth and stomach!"

"No: If you eat them this time of year, you don't get poison ivy in the summer."

"How do you know it?"

"I just know."

James was a water witch or dowser. It was limestone country. No water table. Water ran through tunnels or caves, through underground streams; you hit or you missed. He didn't use a forked stick like most others used. He would lay a willow leaf on his wrist and walk around; when he stopped, it was above water.

"How do you know?"

"The leaf curls down on my arm."

"But it didn't: I watched it."

He shrugged and said, "You don't see it, you feel it."

Whatever, he never missed.

His most amazing trick was the way he could find lost objects. He would take a green switch and follow it until he found your pocketknife or whatever else you lost.

"How?"

"I don't know. I just follow the switch."

And if you hid something, he knew it and wouldn't even look – he just knew it.

My mother somehow managed to raise the money and bought the town hotel. It was an old wooden building facing the town square, and with the hotel came Cora the cook. Cora was the closest friend I ever had in Cave Spring. She was in her 60's, a very large, very human black lady who soon became a member of our family. Not only was she a jewel of a cook, but she was also a jewel of a person.

For a room I had an old butler's pantry off the kitchen. It was small, but one of my chores was washing dishes, and I could come and go by the back door and avoid the lobby.

People who never experienced the old Jim Crow era South cannot seem to understand the relationships and close bonding that often developed between some blacks and some whites.

My grandfather on my mother's side was a Confederate veteran; Henry Wagoneer was black as sin: an ex-slave who had been my granddad's body servant. The black slave child who was born closest to your birthday was given to you as your personal servant. Henry and Grandpa lived together for 86 years. At that age Grandpa died, and Henry lived another ten years. Henry was his dearest friend, his severest critic, and his most trusted advisor. My grandmother died when my mother was four; Uncle Henry took over and mothered the brood. Grandpa was a large man of 6'4" in his bare feet; Henry was small, hardly 5'4", and was the only person in the world my grandpa would not dare to cross.

Contrary to what some folks think these days, Uncle was not a title that designated humble inferiority. It was given as a badge of honor and respect. My grandfather had been named John Baptist Roach; at an early age, resenting the Baptist bit, he had dropped it and picked up Higgens, his mother's family name instead – someone called him Baptist only if he wanted to fight. Uncle Henry, when Grandpa went on the warpath, would stand on his tiptoes, put himself in Grandpa's face, and poke him on the chest, saying, "Now you listen to me, Baptist," and Grandpa would back down and stand corrected.

As a child you might get away with a little sass to Grandpa, but any kid daring to lip off at Uncle Henry got slapped flat – not by Henry, but by the nearest grownup. My grandfather's last request was that his funeral be conducted with one half of the church reserved for the blacks and that Henry be a pallbearer. The family saw to it that his wishes were carried out. It was unheard of in Alabama in the 1920's – the white side of the church was not full, and the black side were hanging in the windows.

This was the John Roach who had stood on the floor of the Alabama legislature and said, "If Alabama is ever going to rise out of its economic depression, we are going to have to bring the blacks up too. You can't keep a man down in a ditch unless you stay there with him. If we keep blacks working for cheaper wages, we will get cheaper wages because then we will have to compete with them." Blacks respected him because he respected them.

On my father's side of the family blacks played an unusual role. His father was also a Confederate vet. Whereas my mother's side of the family owned 6000 acres and 59 slaves and sent their sons to the universities, Grandpa Reynolds's family was "cracker" type and owned six slaves, and Willis Hurd Reynolds could not write his own name. He worked in the fields alongside the blacks.

His wife Jane was educated, and insisted that all of her children go to school. My father's two eldest sisters were born before the Civil War; he was next to the bottom of eleven children, and after they were reared his mother took on four more, two of which were black. It seems there was a man who worked for them, black, who had twin boys about four years old; his wife died and he asked my grandmother if she would care for thin for a week because he had to go on a trip to arrange for their care. He never came back. It was Christmas time and my grandfather called them Tom and Jerry, as that's what he was drinking at the time. She raised them as family, and since there were no schools nearby for blacks in those days, she taught them herself. She must have done a good job because they turned out well, one even becoming a school teacher. They both called her Mom till the day she died.

I am not prejudiced because I was never taught prejudice, and it does have to be taught.

I go into all of this because Uncle Henry comes back into this story later, and it is the reason Cora so quickly became a member of my family.

Times were hard, and my father did not get his usual summer job teaching at the teacher's college. He was despondent and left home swearing that he was going to find some sort of job. He was gone a couple of weeks, and my mother did not know where he was. She did not hear from him. Just over the state line in Selma, Alabama, lived a man named Edgar Cayce who was getting some publicity as "the sleeping prophet." My mother felt he must be an Indian, as only they had this sort of talent – anyway, she wrote him a letter asking about my dad. The letter he wrote back was: "There is really no reason for me to answer this letter. By the time you get this you will have heard from your husband. He will be teaching summer school in Jasper, Alabama." The letter from Dad came the day before the letter from Cayce.

Now at the tender age of fifteen I believed in mental telepathy, mind over matter, and clairvoyance. But God was going the route of Santa Claus – no way.

Since my room was off the kitchen and my chores were washing dishes and maintenance, I hung out with Cora a lot in the kitchen, and Cora believed in ghosties and ghoulies and things that go bump in the night. I will admit that things were happening that I could not explain. On the wall of my butler's pantry stood a large wooden icebox from years before; it took up almost the entire wall. I used it for a closet and storage space. Sometimes at night coming from this old oak box it sounded like muffled voices, and sometimes boards creaked like someone was walking. I thought the old icebox was acting like a sounding box, like on a musical instrument. Cora thought ghost. That old building went back before the Civil War. Sometimes, maybe from the house settling, doors would open by themselves. Cora would pull up a chair near the stove – "Come right in, Mr. King, and sit here by the fire and warm yourself" – then she'd carry on a one-sided conversation with Mr. King.

I saw only an empty chair and heard only Cora's side of the conversation. She sometimes talked about the three dead Yankee soldiers that used to come and talk with her Ma. Well, two of them talked – the other one didn't have no head. I dismissed Cora's stories as flights of fancy, knowing she was completely an honest woman.

Story had it that Mr. King was a previous owner of the hotel who had been struck by lightning while sitting in the front lobby. I didn't see how this could be possible, as I believed that lightning doesn't move in horizontal lines and would have hit the highest point of the building – a hundred years or so can sure improve a story.

Something did happen that I won't even try to explain: Cora and I were sitting in the kitchen one rainy afternoon when a woman in high heels started walking around in the room upstairs. I knew the building was empty. I said, "Somebody's up there," and she said, "Mrs. King. That was her room."

"You might think it's a spook, but somebody real and alive is walking around up there." I went up and searched the entire second floor, complete with under the beds and in the closets. We were alone in the building. High heels make a distinctive sound; I can't imagine what else could make a sound like that.

Years later, after the war, I took my wife down to Atlanta to meet my folks. We went up to Cave Spring to see Cora. Irene, a Yankee gal from Maine, said, "What sort of a man are you – you shook hands with your mother and then gave a fat negro woman a big hug and kissed her." You just can't explain that sort of thing to a Damn Yankee. (In the South it's one word. The difference between a Yankee and a Damn Yankee is: Yankees stay home.) It was Cora, not my mother, who comforted me when fourteen-year-old Betty Caine broke my heart, or wiped my nose when it bled, or held my head when I got drunk. My mother would have killed me had she known.

I will always remember the incident of the peas. Yankees have one variety of pea – green – Southerners have many: blackeye, crowder, whippoorwill, butter peas, etc. I don't remember what kind of peas they were, be we kids didn't like them. Cora told my mother, "I bet you I can get them boys to eat them peas." My mother called her bet. She mashed the peas and formed them into patties which she fried and set on the kitchen table to cool. Then she left the room. When she came back, they were gone. We had stolen and eaten them.

I think I had a mother need in Cora. We could talk about anything. She had only gone to the fourth grade in school, but she had an understanding of human needs and human nature. I suppose now she's somewhere in a beautiful Heaven where there is no injustice, or hatred, or prejudice, a place she believed in with blind faith. I bet she's still laughing.

One day she told me about her Daddy's dream. Her father had been born a slave, the property of a real Southern Colonel. Col. Shorter was the founder of an exclusive girl's school in Rome, Georgia. My sister had attended this college, so I was acquainted with stories about Col. Shorter.

Her father was old and fat and blind, and when I came into the story, dead. He'd had a dream in which Col. Shorter had come to him and told him that during the Civil War, the family valuables had been buried by the left rear corner of the old carriage house. Sherman's army had looted and burned the property. The slaves had buried the stuff with her dad and another man, and they had gone away enjoying their freedom. No one else except the wife knew the location. But the wife died soon after. When Col. Shorter came home from the war, he assumed the stuff had been looted. Her father had assumed that the family had recovered the stuff. In the dream, Col. Shorter wanted her dad to have the stuff dug up and to give half to Shorter College and keep half for himself. He was old and blind. Her brothers laughed at a crazy old man's dream. "John, why don't you go dig it up?" I told several friends (one too many), but the Shorter plantation was miles away, and none of us had a car. Several months slipped away. We finally went, and we found the old foundation. We found the foundation of the old carriage house. We found the left rear corner. We found a big hole where someone had dug, a fairly fresh hole. There was a scrap of rotten wood, rusted metal corner irons and metal straps and an old iron hasp. Scraps of green waxed cloth. The treasure was gone – at least someone had dug up something.

|

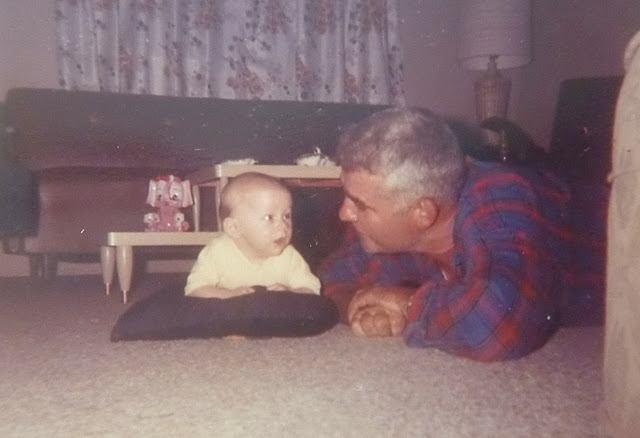

| Little Davey and Big John, long ago (I'm the one on the pillow) |

I would love to read the whole book. I hope I will see it on Amazon soon enough!

ReplyDeletePublish more books please.

ReplyDelete