Nietzsche on Buddhism

The fact is that Nietzsche had no interest whatever in the delusions of the plain people—that is, intrinsically. It seemed to him of small moment what they believed, so long as it was safely imbecile. What he stood against was not their beliefs, but the elevation of those beliefs, by any sort of democratic process, to the dignity of a state philosophy—what he feared most was the pollution and crippling of the superior minority by intellectual disease from below….

In brief, what he saw in Christian ethics, under all the poetry and all the fine show of altruism and all the theoretical benefits therein, was a democratic effort to curb the egoism of the strong—a conspiracy of the chandala against the free functioning of their superiors, nay, against the free progress of mankind….

Socialism, Puritanism, Philistinism, Christianity—he saw them all as allotropic forms of democracy, as variations upon the endless struggle of quantity against quality, of the weak and timorous against the strong and enterprising, of the botched against the fit.

(—H. L. Mencken, in his introduction to Nietzsche’s The Antichrist)

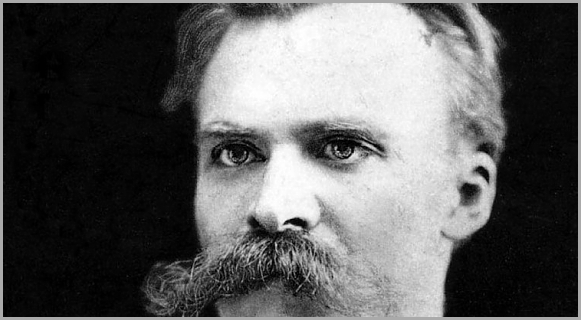

This post is politically incorrect if only because in it I quote Friedrich Nietzsche at length—a man vehemently dedicated to the overthrow and marginalization of such slave moralities as Christianity, communism, and postmodern PC, a man who idealized the ruthless, amoral, and beautiful Superman.

Nietzsche was a strange guy; he was anti-German and vehemently against antisemitism, even to the point of falsely declaring himself to be Polish and of Jewish descent, yet he was a major influence on the ideology of Nazi Germany, practically a prophet of the Aryan Master Race. Before that he was adopted as a kind of prophet of socialism—despite the fact that he despised socialism even more than he despised German culture (he considered “German culture” to be an oxymoron). He was admired by macho socialists like Jack London, back in the day when socialists still had cojones and a spine. Furthermore, he is also considered to be a forerunner of Postmodernism—a fundamental component of “progressivism”—with his assertion that objective truth is an illusion, and actually influenced some of the thinkers of the neo-Marxist Frankfurt School. I have to admit that I don’t like Nietzsche all that much. His writing style is much too rhapsodic and touchy-feely for my tastes, almost like the ravings of a very intelligent and well-educated psychotic (and he did eventually go insane, allegedly due to tertiary syphilis), and his style of composition usually consists of lists of more or less disjointed ideas strung together by poetical flourishes. Also, his disdain for ethical behavior, and apparently even for any wisdom that isn’t lion-like, in his ideal Superman has rubbed me the wrong way in the past—although lately I’ve been seeing a certain amount of ruthless insight in his ideas, a kind of Tantric, wrathful sort of insight. Oh well, a Tibetan Buddhist may tell you that the wrathful deities are just as essential as the peaceful ones. At any rate, I’ve read little of his writings, can’t say that I understand his message all that well, and am certainly no authority on the subject.

One book of his that I have read is The Antichrist, which is considered by those who know to be one of his most coherent and readable. It’s surprisingly easy to read, and I recommend it. The version I read was translated, with a very entertaining introduction, by H. L. Mencken, one of the first English-speaking people to endorse and popularize Nietzsche’s philosophy. The book is not so much an argument against Christ, whom Nietzsche admired to some degree, as an argument against Christianity in general, or rather what Christianity had become in western society. He considered Christianity to have adopted a slave morality, that is, the morality of the servile as opposed to their masters—in fact he considered the Christian ethic of compassion, charity, etc. to be based on ressentiment, that is, feelings of resentment and hatred against the strong and successful that cannot be expressed freely, and so percolate up to the surface in disguised form, like neurotic symptoms.

One reason why I liked the book—and also a big reason why Nietzsche might, and possibly should, become influential again—is that his arguments against Christianity, and late 19th-century socialism also, are even more applicable to early 21st-century neo-Marxism, also known as feminist social justice, “progressivism” (as though decline and fall were progress), PC culture, etc.

But although his take on Christianity could very easily be applied to the new political left, the latest of the perennial risings of the “lower orders,” that is not the purpose of this post. Maybe some other time. The purpose here is simply to show Nietzsche’s attitude toward Buddhism, partly because western Buddhism has been highjacked by PC culture, whereas Nietzsche himself could be viewed as a kind of anti-PC antichrist. In other words, I’m trolling a bit, just having a little fun. Plus I think Nietzsche deserves some recognition now that a system much worse than Christianity is trying to take over western civilization. The book is well worth reading.

Bertrand Russell, in his History of Western Philosophy, set up Gotama Buddha practically as Nietzsche’s opposite, and concocted a little debate between them, with the Buddha defending compassion against Nietzsche’s contempt for it. Russel wrote his book during the Second World War, in which admirers of the Übermensch ideal were attempting to conquer Europe, and he was apparently in a bad mood besides, so he had little good to say about Nietzsche’s glorification of the strong as opposed to the “bungled and botched” masses. Also, Nietzsche does not have a very profound understanding of Buddhism, and in my opinion was not a wise man in a dharmic or spiritual sense. So I’m not presenting his ideas on Buddhism for the sake of teaching people about Dharma. (If you want to learn about the teachings of Gotama Buddha I suggest the Sutta-Nipāta.) I’m doing it, as I say, to show a connection between Buddhism and spirituality on the one hand, and Nietzschean amoral ruthlessness on the other—both may have their place in this world. If there’s no PC taboo against Nietzsche, prophet of the non-PC Superman, there ought to be. The left not only wants to abolish the pitiless yet beautiful Superman, but to render his arising utterly impossible through emasculating civilization with indoctrination, propaganda, and suppressive laws, rendering the human race into a population of docile, gentle, sensitive, caring, mediocre participants in a uniform group mind, like stingless, eunuch social insects; all it will take is a Nietzschean Übermensch or two to arise and crush such a decadent, castrated world.

Anyway, the rest is in his own words, sections 20-23 of The Antichrist, translated by Mencken.

***

In my condemnation of Christianity I surely hope I do no injustice to a related religion with an even larger number of believers: I allude to Buddhism. Both are to be reckoned among the nihilistic religions—they are both décadence religions—but they are separated from each other in a very remarkable way. For the fact that he is able to compare them at all the critic of Christianity is indebted to the scholars of India.—Buddhism is a hundred times as realistic as Christianity—it is part of its living heritage that it is able to face problems objectively and coolly; it is the product of long centuries of philosophical speculation. The concept, “god,” was already disposed of before it appeared. Buddhism is the only genuinely positive religion to be encountered in history, and this applies even to its epistemology (which is a strict phenomenalism). It does not speak of a “struggle with sin,” but, yielding to reality, of the “struggle with suffering.” Sharply differentiating itself from Christianity, it puts the self-deception that lies in moral concepts behind it; it is, in my phrase, beyond good and evil.—The two physiological facts upon which it grounds itself and upon which it bestows its chief attention are: first, an excessive sensitiveness to sensation, which manifests itself as a refined susceptibility to pain, and secondly, an extraordinary spirituality, a too protracted concern with concepts and logical procedures, under the influence of which the instinct of personality has yielded to a notion of the “impersonal.” (—Both of these states will be familiar to a few of my readers, the objectivists, by experience, as they are to me). These physiological states produced a depression, and Buddha tried to combat it by hygienic measures. Against it he prescribed a life in the open, a life of travel; moderation in eating and a careful selection of foods; caution in the use of intoxicants; the same caution in arousing any of the passions that foster a bilious habit and heat the blood; finally, no worry, either on one’s own account or on account of others. He encourages ideas that make for either quiet contentment or good cheer—he finds means to combat ideas of other sorts. He understands good, the state of goodness, as something which promotes health. Prayer is not included, and neither is asceticism.* There is no categorical imperative nor any disciplines, even within the walls of a monastery (—it is always possible to leave—). These things would have been simply means of increasing the excessive sensitiveness above mentioned. For the same reason he does not advocate any conflict with unbelievers; his teaching is antagonistic to nothing so much as to revenge, aversion, ressentiment (—“enmity never brings an end to enmity”: the moving refrain of all Buddhism....) And in all this he was right, for it is precisely these passions which, in view of his main regiminal purpose, are unhealthful. The mental fatigue that he observes, already plainly displayed in too much “objectivity” (that is, in the individual’s loss of interest in himself, in loss of balance and of “egoism”), he combats by strong efforts to lead even the spiritual interests back to the ego. In Buddha’s teaching egoism is a duty. The “one thing needful,” the question “how can you be delivered from suffering,” regulates and determines the whole spiritual diet. (—Perhaps one will here recall that Athenian who also declared war upon pure “scientificality,” to wit, Socrates, who also elevated egoism to the estate of a morality).

***

The things necessary to Buddhism are a very mild climate, customs of great gentleness and liberality, and no militarism; moreover, it must get its start among the higher and better educated classes. Cheerfulness, quiet and the absence of desire are the chief desiderata, and they are attained. Buddhism is not a religion in which perfection is merely an object of aspiration: perfection is actually normal.—

Under Christianity the instincts of the subjugated and the oppressed come to the fore: it is only those who are at the bottom who seek their salvation in it. Here the prevailing pastime, the favourite remedy for boredom is the discussion of sin, self-criticism, the inquisition of conscience; here the emotion produced by power (called “God”) is pumped up (by prayer); here the highest good is regarded as unattainable, as a gift, as “grace.” Here, too, open dealing is lacking; concealment and the darkened room are Christian. Here body is despised and hygiene is denounced as sensual; the church even ranges itself against cleanliness (—the first Christian order after the banishment of the Moors closed the public baths, of which there were 270 in Cordova alone). Christian, too, is a certain cruelty toward one’s self and toward others; hatred of unbelievers; the will to persecute. Sombre and disquieting ideas are in the foreground; the most esteemed states of mind, bearing the most respectable names, are epileptoid; the diet is so regulated as to engender morbid symptoms and over-stimulate the nerves. Christian, again, is all deadly enmity to the rulers of the earth, to the “aristocratic”—along with a sort of secret rivalry with them (—one resigns one’s “body” to them; one wants only one’s “soul”...). And Christian is all hatred of the intellect, of pride, of courage, of freedom, of intellectual libertinage; Christian is all hatred of the senses, of joy in the senses, of joy in general....

***

When Christianity departed from its native soil, that of the lowest orders, the underworld of the ancient world, and began seeking power among barbarian peoples, it no longer had to deal with exhausted men, but with men still inwardly savage and capable of self-torture—in brief, strong men, but bungled men. Here, unlike in the case of the Buddhists, the cause of discontent with self, suffering through self, is not merely a general sensitiveness and susceptibility to pain, but, on the contrary, an inordinate thirst for inflicting pain on others, a tendency to obtain subjective satisfaction in hostile deeds and ideas. Christianity had to embrace barbaric concepts and valuations in order to obtain mastery over barbarians: of such sort, for example, are the sacrifices of the first-born, the drinking of blood as a sacrament, the disdain of the intellect and of culture; torture in all its forms, whether bodily or not; the whole pomp of the cult. Buddhism is a religion for peoples in a further state of development, for races that have become kind, gentle and over-spiritualized (—Europe is not yet ripe for it—): it is a summons that takes them back to peace and cheerfulness, to a careful rationing of the spirit, to a certain hardening of the body. Christianity aims at mastering beasts of prey; its modus operandi is to make them ill—to make feeble is the Christian recipe for taming, for “civilizing.” Buddhism is a religion for the closing, over-wearied stages of civilization. Christianity appears before civilization has so much as begun—under certain circumstances it lays the very foundations thereof.

***

Buddhism, I repeat, is a hundred times more austere, more honest, more objective. It no longer has to justify its pains, its susceptibility to suffering, by interpreting these things in terms of sin—it simply says, as it simply thinks, “I suffer.” To the barbarian, however, suffering in itself is scarcely understandable: what he needs, first of all, is an explanation as to why he suffers. (His mere instinct prompts him to deny his suffering altogether, or to endure it in silence.) Here the word “devil” was a blessing: man had to have an omnipotent and terrible enemy—there was no need to be ashamed of suffering at the hands of such an enemy.—

At the bottom of Christianity there are several subtleties that belong to the Orient. In the first place, it knows that it is of very little consequence whether a thing be true or not, so long as it is believed to be true. Truth and faith: here we have two wholly distinct worlds of ideas, almost two diametrically opposite worlds—the road to the one and the road to the other lie miles apart. To understand that fact thoroughly—this is almost enough, in the Orient, to make one a sage. The Brahmins knew it, Plato knew it, every student of the esoteric knows it. When, for example, a man gets any pleasure out of the notion that he has been saved from sin, it is not necessary for him to be actually sinful, but merely to feel sinful. But when faith is thus exalted above everything else, it necessarily follows that reason, knowledge and patient inquiry have to be discredited: the road to the truth becomes a forbidden road.—Hope, in its stronger forms, is a great deal more powerful stimulans to life than any sort of realized joy can ever be. Man must be sustained in suffering by a hope so high that no conflict with actuality can dash it—so high, indeed, that no fulfilment can satisfy it: a hope reaching out beyond this world. (Precisely because of this power that hope has of making the suffering hold out, the Greeks regarded it as the evil of evils, as the most malign of evils; it remained behind at the source of all evil.)**—In order that love may be possible, God must become a person; in order that the lower instincts may take a hand in the matter God must be young. To satisfy the ardor of the woman a beautiful saint must appear on the scene, and to satisfy that of the men there must be a virgin. These things are necessary if Christianity is to assume lordship over a soil on which some aphrodisiacal or Adonis cult has already established a notion as to what a cult ought to be. To insist upon chastity greatly strengthens the vehemence and subjectivity of the religious instinct—it makes the cult warmer, more enthusiastic, more soulful.—Love is the state in which man sees things most decidedly as they are not. The force of illusion reaches its highest here, and so does the capacity for sweetening, for transfiguring. When a man is in love he endures more than at any other time; he submits to anything. The problem was to devise a religion which would allow one to love: by this means the worst that life has to offer is overcome—it is scarcely even noticed.—So much for the three Christian virtues: faith, hope and charity: I call them the three Christian ingenuities.—Buddhism is in too late a stage of development, too full of positivism, to be shrewd in any such way.—

* At least in the sense of self-torture (my note)

**That is, Pandora’s Box. (Mencken’s note)

Comments

Post a Comment

Hello, I am now moderating comments, so there will probably be a short delay after a comment is submitted before it is published, if it is published. This does have the advantage, though, that I will notice any new comments to old posts. Comments are welcome, but no spam, please. (Spam may include ANY anonymous comment which has nothing specifically to do with the content of the post.)