Reflections on the New Ananda Temple Which May Never Be Built

AFTER the journey of fifteen days that has been mentioned, you reach the city of Mien [Bagan, in Myanmar], which is large, magnificent, and the capital of the kingdom. The inhabitants are idolaters, and have a language peculiar to themselves. It is related that there formerly reigned in this country a rich and powerful monarch, who, when his death was drawing near, gave orders for erecting on the place of his interment, at the head and foot of the sepulcher, two pyramidal towers, entirely of marble, ten paces in height, of a proportionate bulk, and each terminating with a ball. One of these pyramids was covered with a plate of gold an inch in thickness, so that nothing besides the gold was visible; and the other with a plate of silver, of the same thickness. Around the balls were suspended small bells of gold and of silver, which sounded when put in motion by the wind. The whole formed a splendid object. The tomb was in like manner covered with a plate, partly of gold and partly of silver. This the king commanded to be prepared for the honor of his soul, and in order that his memory might not perish. The Grand Khan, having resolved upon taking possession of this city, sent thither a valiant officer to effect it, and the army, at its own desire, was accompanied by some of the jugglers or sorcerers, of whom there were always a great number about the court. —Marco Polo, on his visit to Bagan (and the “pyramids” were probably bell-shaped pagodas)

Venerable U Kosalla, the abbot of the Burmese monastery in French Camp, California, wants to build a pagoda. He wants to build a pagoda in accordance with the tradition of his lineage: his teacher venerable Kyauk Hsin Sayadaw had a huge one built in upper Myanmar, as did his teacher’s teacher, the founder of our tradition, venerable Taungpulu Sayadaw.

Because U Kosalla lives in America, however, he can’t go about it in the same way as in Burma/Myanmar. For starters, building things in America is much more difficult and expensive: not only do building materials and labor cost much more, but there are the Byzantine complexities of county planning commissions, zoning laws, building codes, inspectors of all sorts, soil testing, and the non-Buddhist sentiments of the neighbors. In fact even when Burma was struggling under a brutal military dictatorship (and I ought to know because I lived there during it for many years), it was in some ways much more free than the USA, allegedly “the home of the free.” In Burma if somebody wants to build a house, or a pagoda, they just get the funds, the materials, and the workers together and they go ahead and build the thing, much as was the case in America long ago. If it collapses after one week well, that’s just too bad. But in America now, as pretty much everywhere in the west, it’s different. One of the main freedoms that Americans have that the Burmese under the military regime did not enjoy was expressing seething hatred and rage, let alone disapproval, against the government…but I digress.

So, as I say, venerable U Kosalla has his heart set on building a pagoda here in French Camp, California, just a few miles south of Stockton. And perhaps because of the different conditions here, the pagoda he hopes to build is very different from the bell-shaped piles of bricks so common in his native land (in fact bell-shaped pagodas may be seen all over the Buddhist parts of Burma, which is most of it). Rather than the standard stupa aforementioned (the bell-shaped pagoda), he wants to build a pahto—that is, a kind of ornate temple of the type that was in fashion in Burma almost a thousand years ago, as may be seen today in the ancient city of Bagan, the capital of the first Burmese Empire. In fact U Kosalla wants to build a small-scale replica of one of the most glorious temples in Bagan, the Ananda Hpaya.

|

| the original Ananda Temple in Bagan/Pagan, Myanmar/Burma |

I’ve been to the original Ananda temple, and it is indeed glorious. It’s beautiful. It was built in the early 12th century under the patronage of Kyansittha, second ruler of the Pagan dynasty, and Shin Arahan, the Buddhist missionary monk primarily responsible for the conversion of the Burmese to Theravada Buddhism. Not only is it glorious and beautiful, it is huge; so venerable U Kosalla has desired to build a smaller version, only eighty feet or so in height, about half as tall as the original monument.

And so, with this lofty ambition in his heart, U Kosalla and his supporters acquired a largish, flat plot of land in California’s central valley, surrounded by small farms and almond orchards. The trouble is, though, that some of the neighbors, I assume mostly conservative types, do not want a huge temple in their neighborhood; and in fact they have fought against the temple, and also a proposed center for meditation retreats to be associated with the temple, from the beginning, as soon as they became aware of U Kosalla’s intentions.

The first attempts to get permission to build were shot down years ago, at the insistence of the aforementioned neighbors. Just recently there was another attempt, which squeaked by with a vote of 3-2 in favor, but later it was overruled after vehement appeals from the same few neighbors. So, instead of doing the reasonable thing and selling this place and starting again in an area that is more isolated or more “liberal,” i.e. not surrounded by narrow-minded conservative farmer types, or just giving up on the idea, the Burmese plan to go to the county planning commission yet another time. One option is suing based on the First Amendment of the US Constitution, which has been proposed by some supporters of this monastery, though of course that would cause the strained relationship with the least tolerant of the neighbors to become even worse.

At the hearing I attended recently, wearing a plague mask and sitting at a distance from everyone else by decree, the two most vociferous neighborhood antagonists raised serial objections in protest against the proposed developments of the monastery land; after one objection was debunked by the engineers and architects testifying for the monastery’s side they’d simply move onto another, often trivial objection (“The road is too small!” “The monks don’t water their plants!”). This in itself was pretty fair evidence to me that the objections were not the real reason why they didn’t want the pagoda or the meditation center. The real reason, as far as I could see, was simply that a bunch of conservative western farmer types didn’t want weird foreigners building weird buildings and doing weird ceremonies in their community. It’s not necessarily racism (though some of the Burmese called it that), but almost certainly some plain old-fashioned xenophobia, or instinctive dislike of the foreign, exotic, or unfamiliar.

Enough of the county planning commissioners appear to hold similar sentiments. Nobody on the opposing side even knew what a meditation center is supposed to be, and the Burmese were too clueless to explain the case clearly; instead they stood up and all gave cringeworthy prepared speeches full of cliches like “all walks of life,” as though they were reading a junior high school book report. I kept wanting to stand up during the hearing and butt in by explaining what a meditation center is, and what goes on at such places (quiet meditation), but I wasn’t called on to speak, so I didn’t.

Actually I am rather ambivalent on this whole issue. I have no skin in the game, so to speak, and also I can relate to both sides of the contention.

On the one hand, the scaled-down Ananda would almost certainly be one of the most magnificent Buddhist temples in North America, assuming that it were built well. It could really be a glorious monument, something worth coming from far away to see, sort of like the replica of the Parthenon I’ve been told is standing near Nashville, Tennessee. Also the meditation center, assuming that the organizers invite qualified teachers and maintain some actual discipline, could be of great value to everybody, “all walks of life,” not just to devout Burmese Buddhist immigrants and their families. Meditation truly is invaluable for cultivating mental strength and stability as well as wisdom, and can change lives for the better. Furthermore, the Burmese Buddhist community is exceptionally good-hearted and well behaved, and the devout Buddhists who come to the temple or the meditation center would certainly not be rowdy troublemakers, though the occasional festivals associated with the pagoda especially would produce some noise and entropy. (Though as I write this there is loud, awful Mexican music being blasted at a fiesta in the distance.) One would think that in America, with freedom of religion and peaceful assembly, and a multitude of ethnic cultures, there should be no problem with this.

On the other hand, I have gradually been developing a more right-wing, nationalistic appreciation of the value of a unifying tradition to keep a culture and a nation strong and vital, a kind of unifying spirit, and I can see the disintegrating social effects of multiculturalism, as do the neo-Marxists and globalists that endorse it; and I also feel that the people of a community should have the right to decide, more or less democratically, what sort of buildings and monuments are built there. It is also true that the occasional Burmese Buddhist festivals celebrated at the pagoda can be a minor nuisance to neighbors with no interest in pagoda festivals.

I really do think the temple would be totally cool-looking, a magnificent monument. But I can accept either way, for the reasons already stated, and also because I very probably wouldn’t be here by the time it was built anyway, but would just be here for some of the noise and commotion of construction. The Burmese are a good-hearted and beautiful people, but still I fit in here only somewhat better than the monastery fits into a conservative farming community. Some of the Burmese supporters even call me the “foreign monk,” when technically I’m the only American-born person living here. I aspire before much longer to move somewhere more blatantly, traditionally American—more spiritually bankrupt maybe, but at least I’ll be somewhat less of an outsider.

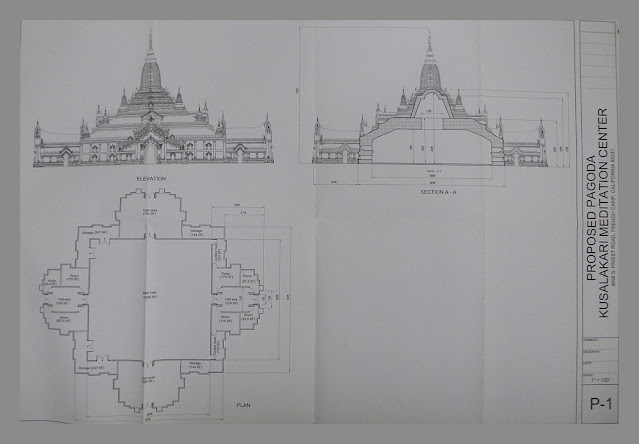

|

| plans for the proposed temple |

Thank you for the news Ven. Pannobhasa! The temple is very sensually pleasing, and it would be magnificent if it was built!

ReplyDeleteWe need as many temples as we can get in the battle against ignorance and delusion!

If, after over 20 years practice, Mahathera Pannobhasa feels like an outsider at a Buddhist centre where he lives, then I suspect Mahathera will feel like the same outsider wherever he is living - spiritually bankrupt or not; which does of course raise the question of what one's fundamental motivation is for living where one lives or doing what one does.

ReplyDeleteAs another "outsider" I have often bemoaned the fact that I chose not to enter the Therevada monastery I was invited to join, so your statement regarding being an outsider in a monastic setting is appreciated though shattering my illusions of harmonious monastic living and joyous friendship (somewhat tongue in cheek).

Some of us, in evolutionary terms, are "un-fit's" no matter where we are or what we do - we best come to terms with that and choose the mode of living that suits us best - for all the good and bad that comes with those decisions.

Yes, living isn't easy. Being an "outsider" or an "un-fit" complicates things even more.

Good luck to you either way, whether you end up staying in a monastery as an "outsider" or choose to move back in to "traditional-America" as an "un-fit" (if that can be found at this point) - just don't move into an apartment next to a main road or a Burger King ! - though many would call that an advantage I suspect!

Not big problems anyway, more like some litter and noise on Buddhist holidays, plus maybe encouraging a cat population problem by monks compassionately feeding stray animals.

ReplyDelete